“That is it! We cannot wait anymore. We are going to Hama, this morning.”

My mother stood facing both of us, my twin and I, helpless and without words. It was Tuesday 16 March, two weeks after Hafez al-Assad reopened the sealed city of Hama after he massacred around forty thousand people in February 1982. My mother had vetoed our decision to travel there several times before, and we had yielded to her wishes, but not today. Hama was our childhood city that we used to visit almost monthly after the family moved to Damascus so we may attend college. We felt the mourning city calling to us. When you feel something so powerful, you have to answer.

“What are you going to do there? It is not even safe! Just to measure the distance between Hama and Damascus?” my mother said angrily. She just stood there, frightened she might not see either of us again, but realizing how determined we were. She was right. It was risky, suicidal even. Assad’s intelligence officers were arresting people at the Qabon Bus Station, east of Damascus—merely for asking whether the road to Hama had been reopened. I had a friend who was arrested under this pretext, sent to the Hama Intelligence branch, forced to falsely confess allegiance to the opposition, sent to Tadmor Prison, and finally condemned to spend twenty long, torturous years there, where we later met.

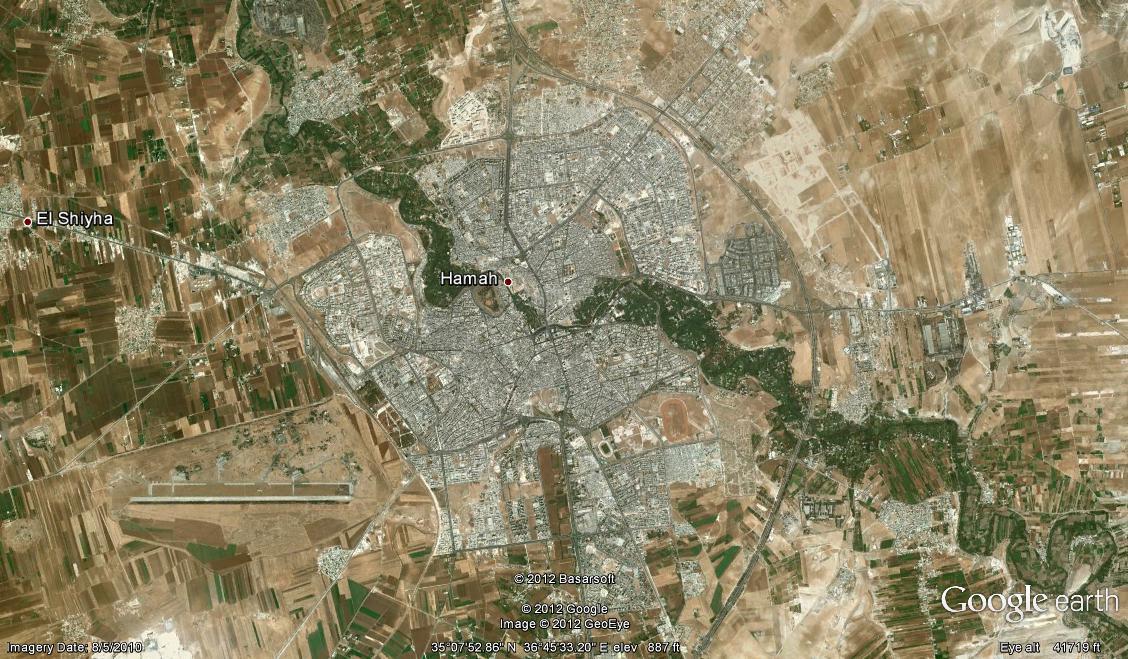

Hama is divided by the Orontes (Asi) river into northern Hader and southern Souk. Image from Google.

We could not just sit in Damascus receiving horrible stories of death and destruciton for over a month. We had to see for ourselves. “Mom, pray for us,” we said while closing the door behind us. We were silent the entire way to the old bus station east of Damascus. Fear was in our hearts but we overcame it with determination. We asked, “Can we get to Hama?” A man answered, “Yes, just get in the bus. We are leaving shortly.” Our pounding hearts began to accelerate as we crossed Homs, and an aura of bleak silence overtook the few people on the bus. Everyone was avoiding eye contact, and all eyes were fixed on the road.

Hama is situated in a valley, so you cannot catch sight of the city from afar until you reach a hill at the midpoint between Rastan and Hama. My heart still squeezes as I remember the very first glimpse of the ruined city. A layer of clouds covered the city but a small window allowed a few strong sun rays to pierce the gray sky. Dust was everywhere, billowing out of the many monstrous bulldozers Assad had sent to finish what his tanks had failed to do. The three helicopters that regularly hovered over the city, between the western military airport and the eastern mount of Ali Kasoon, were absent. The lack of helicopters in itself was a sufficient sign that the city was not well.

The Kilani district east of river and citadel was utterly flattened along with its treasures by Asad. Image from Google.

There were no domestic pigeons circling over the houses, just humid dust. A heavily-armed checkpoint was still near the military intelligence branch. Harsh, criminal eyes screened the movement on the highway from behind anti-aircraft guns. There were no signs of tanks except the deep traces of their chains embedded within the destroyed paved asphalt. The passengers were dumbstruck. All eyes oscillated from right to left. No comments. The main southern entrance to the city past the National Hospital had been erased of any sign of life. The first glimpse of destruction was the cemetery. Not a single tombstone was in its place. I had to pay the cemetery a number of visits in later months, looking in vain for my father’s grave. We could not wait until the bus reached its destination, so we asked the bus driver to drop us at the entrance of the Veterinary School entrance. It was 10 a.m.

From that elevated point of the city, the scene was of an earthquake. As we went down Alamain Street, which ends in Asi Square, all the shops were empty and burned down. Many metallic-sheet shop doors were bent out of their tracks, seemingly due to the heavy pressure of explosions. The balconies were destroyed and the windows were stripped out of their wooden frames. Not a single wall was without holes of different sizes—a reflection of the variety of bullets and rockets that Assad forces had used against the city. Walls and doors everywhere were dotted with countless bullets holes indeed. The permeating smell was of humid, burned flesh. The main Sheikh Alwan Mosque and the city’s clock tower—icons of Hama—had both disappeared, only to be rebuilt years later by Assad himself. We heard that a sniper from the defendants of the city dwelt in that tower for days wreaking havoc on Assad forces until they were able to trace his bullets. Then, they completely bombed the tower.

Where to go from here? We decided to head west and walk to the March Eight Street, a major commercial hub of the city. It is a straight street lined with four-story buildings on both sides. Still no people were around but a few women, children, and tired elderly. Again, all the shops in the commercial Marabit and the Long Market, an iconic bazaar with hundreds of shops that sold everything from gold and textiles to spices, were looted and burned. The March Eight Street showed signs of heavy battles. Assad forces wanted to demolish it by destroying the huge concrete, load-bearing, cylindrical pillars of the buildings so they would collapse against each other. Later, Assad’s construction companies (sent to redesign the city) had to inject cement to reenforce the cracked buildings’ pillars and add extra steel ones to prevent the collapse they had intended. Even a centuries-old small mosque in the middle of that street, where memories of early childhood reside, was blown up and turned into a heap of rubble and scattered blocks of rock. We continued, ascending the Jizdan Hill. We saw pockets of destroyed houses and signs of severe fights that had taken place in the Wadi district.

We walked aimlessly from street to alley and back to a major street again. There was nobody around but a few women and children. All shops were looted and burned. There was complete silence except for sporadic gun fire heard from different parts of the city. We walked down toward the city center to pass by the Sultan Mosque. One big hole punctured the dome and there were no minarets. If a mosque was ever to be named the "Mosque of the Two Fallen Minarets,” it would be this one. The first minaret fell in April 1964, in the first uprising against the rule of the extremist Baath Party.

We climbed the stairs into the apartment of one of our high school friends. Doors were open, the floor curved up due to severe burning and seemed unsafe to walk over. We walked along the walls of the central room to what appeared to be a bedroom. It was a small room with a bed covered with ashes. A piece of what looked like a human skull was on it. I picked it up. It disintegrated between my fingers. Was it our friend`s?

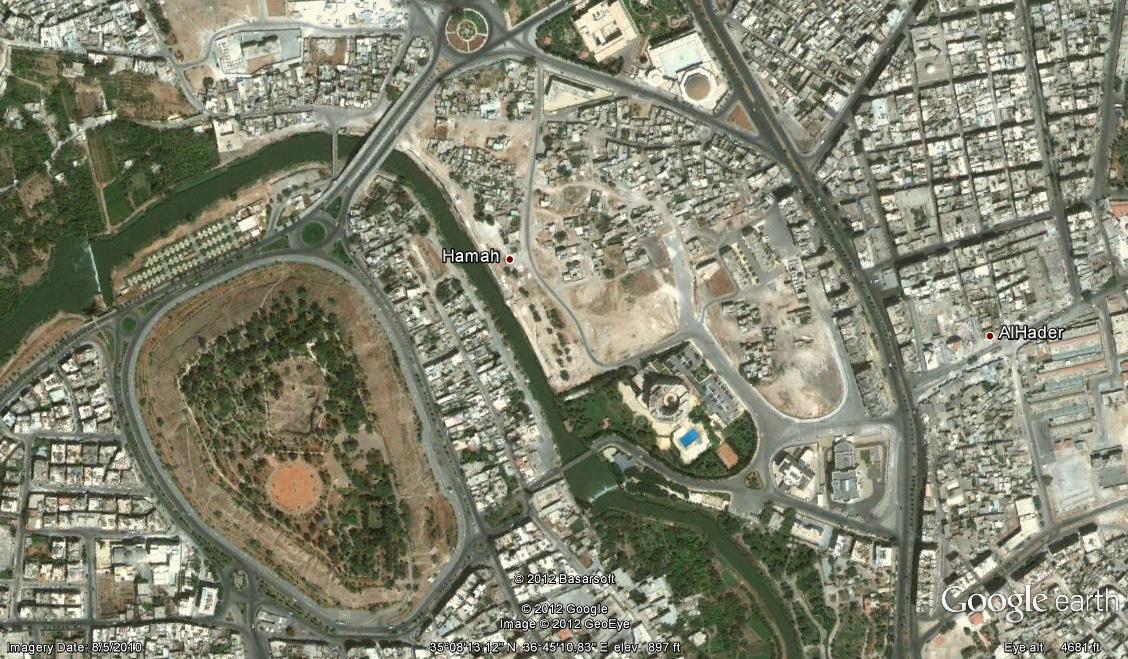

Long silence prevailed between us. He was such a nice guy! How many times did we play football together? How often did we meet on the way back home cheering each other from a distance? I still remember his elegant appearance, his confident, upright posture and reserved yet welcoming smile. We later found out his fate. He died of his wounds in his bed after he tried to prevent Assad sodiers from taking his father. He was shot. The remaining members of his family were rounded up in a shop with tens of men from the neighborhood and were burned alive. We rushed out of the building to have enough time to roam the Hader district, the other half of Hama, north of the Orontes River. The famous, ancient waterwheels of Hama were dry and silent.

Crossing the main bridge connecting the Asi Square to the Hader’s main street, we were stunned. The area truly endured an Assad-made earthquake. The huge six-floor complex overseeing the historical Hader was almost completely destroyed. Massive artillery holes riveted everywhere. There was no asphalt. The tank chains had left nothing but mud. Bullet holes of every size caused us to trip and tumble while walking. Tens of different-sized rockets had stabbed the ground here and there with their fins pointing upwards. Our biggest concerns were the historic Kilani buildings that had been the iconic pride of Hama for centuries. All of them were destroyed.

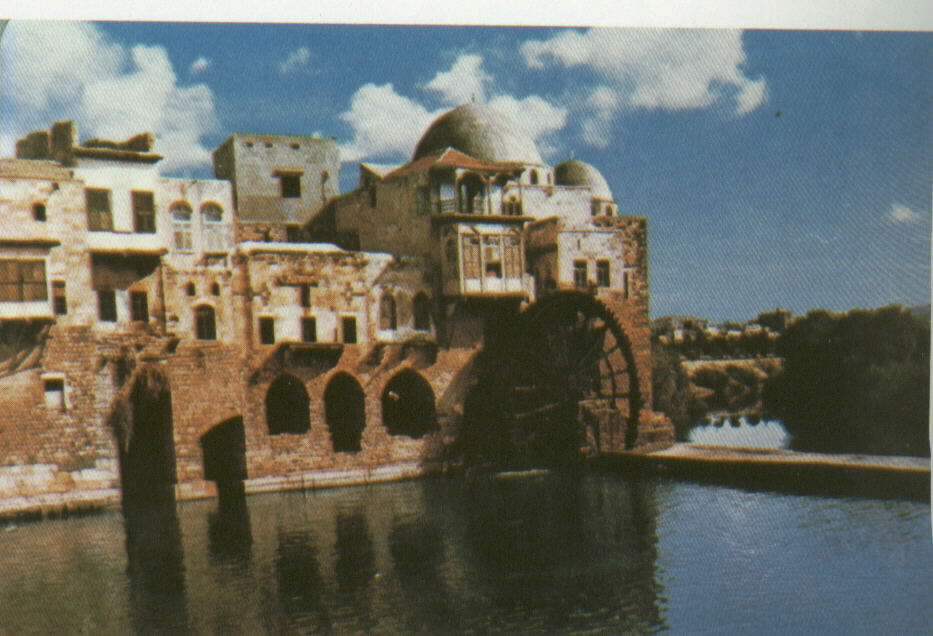

The Kilani Corner, an icon of Hama, before the massacre of 1982. Image from unknown archive.

The extent of the destruction had left the street level so high that the tops of the doors had turned into windows instead. We dangled into one of the deserted homes. An old home with a beautiful courtyard, a pond, and a fountain was covered with dust and scattered rocks. Among the rubble laid a notebook. I picked it up. It belonged to a college student. Where was he now? Where are the people? Who knows! We found out later that Assad’s troops had rounded up all the males they were not able to butcher and distributed them into major detention camps: the airport, the textile factory, the mills, the porcelain factory, and the technical high school, among many others. The house opened to an adjacent home via a hole in the shared wall, a technique used by Hama fighters to evade Assad forces in the unsafe streets.

A number of bulldozers with drivers in uniforms were demolishing what the month-long bombardment had missed. We hid from them when we saw the military uniforms. We heard one stop his truck and happily call to another, “Look what I found! Canned ghee!” The other cheered him for his valuable discovery! From our angle, we watched the bulldozers turn the Kilani district turned into a flat area. The machines were acting non-stop as if they were in a desert, not in a UNESCO-protected World Heritage historical site.

The Kilani Corner, summer 1982. Image from unknown archive.

The air was heavy with dust. The only sounds were the whistling of the bulldozers moving backward along with sporadic gunfire. There were no people around except us.

We reached the eastern district of Hader, the neighborhood where we grew up. Cars were crushed by the tanks that had rolled over them. The Eastern Mosque was destroyed except for its qibla (the direction towards the Kaaba in Mecca, toward which Muslims turn for daily prayers). It carried a Quranic verse stating “Only the ones who believe in Allah and the Day of Judgment build the mosques of Allah.” At the edge of the orchards, tens of shoes and slippers were spread out on the ground: what remained of people after they were shot dead then taken away.

It was almost sunset, and we had to rush back to the Asi Square. The same bus was moving slowly, looking for survivors to pick up. We climbed into the bus at the last minute, gasping. The driver refused to take our money. He sadly said, “Thanks to God for your safety.” He was right. Assad forces were still arresting people from the streets we had just walked. Many of those people disappeared forever. Our logic at the time was that we should worry about the city: forget ourselves!

My twin and I were not talking to each other. There were no words! We passed through Homs. Everything was normal. The city bustled with people in the crowded markets just half an hour away from its dead twin city. When we arrived to Damascus, we thought the buildings had holes, a visual illusion that Hama had marked our eyes with. We noticed it in Homs, as well. We rubbed our eyes a little to make sure we were okay.

We knew that the human loss was too massive to bear, but the destruction of historical Hama left a wound which would never heal. Even the subsequent twelve years I spent in Assad’s hellish detention camps did not overshadow the loss of Hama. I visited Hama numerous times after my release but could not reconcile that loss.

The Kilani Corner, nowadays. A hotel (left) was built over the site! Image by Bara Sarraj.

Every time I visited the city, I had to leave by sunset: a time seemingly set by that first visit—as if the souls of thousands of martyrs were chasing me, asking for revenge. Or an answer.